An MIT-led team has created an AI algorithm that can finally map the brainstem’s tiny white matter pathways on standard MRI scans. The tool could help doctors track diseases like Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injury, and even monitor coma recovery.

For decades, some of the brain’s most critical control circuits have been hiding in plain sight.

Deep in the brainstem, tiny bundles of nerve fibers help regulate breathing, heart rate, sleep, movement and consciousness. But because these bundles are so small and surrounded by fluid and motion from every heartbeat and breath, standard imaging tools have struggled to see them clearly.

Now an MIT-led team has developed an artificial intelligence tool that can automatically map eight of these brainstem fiber bundles on diffusion MRI scans, opening a new window into conditions ranging from Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis to traumatic brain injury and coma.

The software, called the BrainStem Bundle Tool (BSBT), is publicly available and was described in a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by researchers from MIT, Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital.

The work targets a part of the brain that has been largely overlooked by imaging, according to Mark Olchanyi, a doctoral candidate in MIT’s Medical Engineering and Medical Physics Program who led the research.

“The brainstem is a region of the brain that is essentially not explored because it is tough to image,” Olchanyi said in a news release. “People don’t really understand its makeup from an imaging perspective. We need to understand what the organization of the white matter is in humans and how this organization breaks down in certain disorders.”

Co-senior author Emery N. Brown, the Edward Hood Taplin Professor of Computational Neuroscience and Medical Engineering at MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science and the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT, who is Olchanyi’s thesis supervisor, noted that the advance could reshape how scientists and clinicians study vital functions.

“The brainstem is one of the body’s most important control centers. Mark’s algorithms are a significant contribution to imaging research and to our ability to understand the regulation of fundamental physiology. By enhancing our capacity to image the brainstem, he offers us new access to vital physiological functions such as control of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, temperature regulation, how we stay awake during the day and how we sleep at night,” Brown, who is also an anesthesiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor at Harvard Medical School, said in the news release.

A new way to see hidden wiring

The brain’s communication highways are made of long nerve fibers called axons, bundled together and wrapped in a fatty coating known as myelin. These bundles form the brain’s “white matter,” which carries signals between regions.

Diffusion MRI is a specialized type of scan that tracks how water moves in tissue. In white matter, water tends to move along the length of axons rather than in all directions, allowing scientists to infer the paths of fiber bundles.

But in the brainstem, those bundles are tiny and packed tightly together. Their signals are easily obscured by the motion of blood and cerebrospinal fluid and by the physical movement of breathing and heartbeats. That has made it extremely difficult to separate one bundle from another in living patients.

Olchanyi set out to change that as part of his thesis work on the neural basis of consciousness.

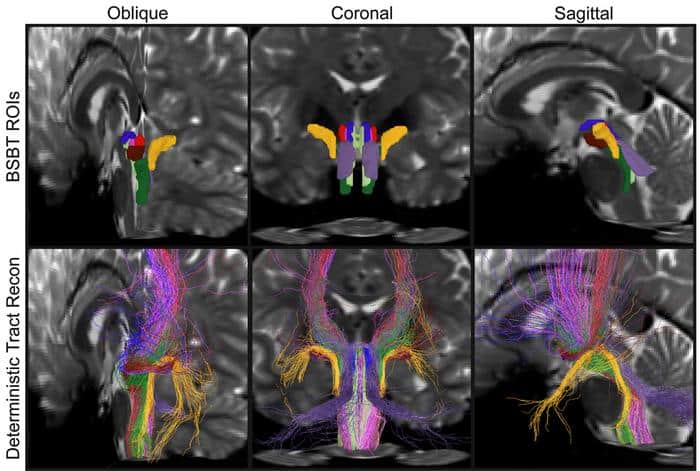

BSBT starts by tracing fiber bundles that enter the brainstem from neighboring structures higher in the brain, such as the thalamus and cerebellum. Using those trajectories, it builds what the team calls a “probabilistic fiber map.” An AI module known as a “convolutional neural network” then combines that map with multiple channels of MRI information from inside the brainstem to distinguish eight specific bundles.

To teach the network what to look for, Olchanyi used 30 diffusion MRI scans from healthy volunteers in the Human Connectome Project. Experts had manually annotated the bundles in these scans, giving the AI a detailed reference.

The team then checked BSBT’s performance against “ground truth” data from post-mortem human brains, where the bundles could be clearly seen using microscopic examination or extremely slow, ultra-high-resolution imaging.

After training, the tool could automatically identify the eight bundles in new scans.

Caption: Detail from a figure in the study shows brainstem bundle regions of interest In three different cross-sections of a brain, as automatically determined by BSBT (top row) vs. a “ground-truth” method.

Credit: Mark Olchanyi/MIT Picower Institute

Stress-testing the AI

To make sure the algorithm would hold up in real-world use, Olchanyi and his colleagues put it through a series of tests.

In one experiment, they asked BSBT to find the same bundles in 40 volunteers who each had two scans taken two months apart. The tool consistently located the same bundles in each person across both scans.

The team also ran BSBT on multiple independent datasets, not just the Human Connectome Project images, to see if it generalized beyond one type of scan. In addition, they systematically disabled different parts of the neural network to see how each component contributed to performance.

“We put the neural network through the wringer,” Olchanyi added. “We wanted to make sure that it’s actually doing these plausible segmentations and it is leveraging each of its individual components in a way that improves the accuracy.”

Tracking disease and injury in the brainstem

Once BSBT was trained and validated, the researchers turned to a key question: Could this new ability to separate brainstem bundles provide useful biomarkers of disease and injury?

They applied the tool to diffusion MRI datasets from patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis (MS) and traumatic brain injury (TBI), comparing patients with healthy controls and, in some cases, comparing patients to themselves over time.

For each bundle, BSBT measured volume and a standard diffusion MRI metric called “fractional anisotropy,” which reflects how strongly water movement is aligned with the direction of the fibers. Lower fractional anisotropy typically indicates damage or loss of structural integrity in white matter.

Across conditions, the algorithm found consistent patterns of change.

In Alzheimer’s disease, only one of the eight bundles showed a significant decline. In Parkinson’s disease, three bundles showed reduced fractional anisotropy, and another bundle lost volume over a two-year follow-up period. Patients with MS had the largest fractional anisotropy reductions in four bundles and volume loss in three. In TBI, most bundles did not shrink, but many showed reduced fractional anisotropy, suggesting subtle structural damage without major volume loss.

When the team compared BSBT to other classification methods, the new tool proved more accurate at distinguishing patients from healthy controls based on brainstem white matter features.

The authors concluded that BSBT can be “a key adjunct that aids current diagnostic imaging methods by providing a fine-grained assessment of brainstem white matter structure and, in some cases, longitudinal information,” potentially giving clinicians a more sensitive way to monitor disease progression or treatment effects.

A window into coma recovery

One of the most striking demonstrations came from a single patient: a 29-year-old man who suffered a severe traumatic brain injury and remained in a coma for seven months.

Using diffusion MRI scans taken during that period, Olchanyi applied BSBT to track the patient’s brainstem bundles over time. The analysis revealed that the bundles had been displaced by the injury but not severed. Over the months, the lesions affecting those bundles shrank to about one-third of their original volume, and the bundles gradually shifted back toward their normal positions.

BSBT “has substantial prognostic potential by identifying preserved brainstem bundles that can facilitate coma recovery,” the authors wrote. In other words, being able to see which pathways are still intact, even if damaged, could help doctors better estimate a patient’s chances of waking up and recovering function.

What comes next

Because BSBT is publicly available, other research groups and clinicians can begin testing it in their own datasets and patient populations. Over time, that could help determine how best to integrate brainstem bundle mapping into routine imaging for neurodegenerative diseases, MS, TBI and disorders of consciousness.

More broadly, the work highlights how AI can push the limits of what existing imaging technologies can reveal. By extracting subtle patterns from noisy data, tools like BSBT can turn previously “invisible” structures into measurable, clinically relevant features.

For patients and families facing brain diseases and injuries that affect the most basic functions of life, that new visibility could eventually translate into earlier diagnoses, more precise monitoring and better-informed decisions about care and recovery.

Source: MIT Picower Institute