Engineers at the University of Pennsylvania have designed a solar-powered data center that would orbit Earth on long, plant-like tethers. The concept aims to move energy-hungry AI computing off the ground and into space using existing technologies.

As artificial intelligence systems devour more electricity and water on Earth, engineers at the University of Pennsylvania are looking up — way up — for a solution.

A team at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science has developed a detailed design for solar-powered data centers that would orbit Earth, using long, flexible cables called tethers to hold thousands of computing units in place. The concept is meant to be ambitious enough to meaningfully offload AI computing from the ground, but simple enough to build with technologies that already exist.

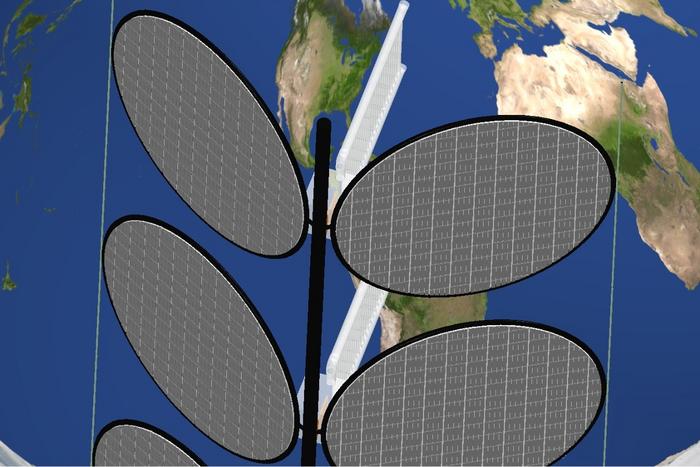

The proposed orbital data center resembles a giant, leafy plant floating in space. Long, vertical columns of hardware hang along tethers, while wide, thin solar panels branch out like leaves to capture sunlight. The system is designed to host thousands of identical computing nodes, each carrying chips, solar panels and cooling equipment, all linked together along a cable.

Caption: A schematic of the proposed orbital data center design, which resembles a leafy plant, with solar panels branching out from long columns that hold computing hardware.

Credit: Igor Bargatin, Dengge Jin, Zaini Alansari, Jordan R. Raney

The key innovation is how the structure stays oriented in space. Traditional satellite designs often rely on motors and thrusters to keep solar panels pointed at the sun. That adds weight, complexity and energy use — all major drawbacks when you are trying to scale up.

Senior author Igor Bargatin, an associate professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics (MEAM), noted the Penn design takes a different approach.

“This is the first design that prioritizes passive orientation at this scale,” he said in a news release.

In orbit, tethers behave in a special way. Gravity pulls one end of the tether slightly toward Earth, while the centrifugal effect of orbital motion pulls the other end outward. Those competing forces stretch the cable taut and naturally align it in a vertical orientation. Engineers have studied tethers for decades, and they have been tested in space, which is one reason the Penn team sees them as a realistic building block.

Because the structure hangs along a tether, the computing nodes can be added one after another. Bargatin compares it to a simple piece of jewelry.

“Just as you can keep adding beads to form a longer necklace, you can scale the tethers by adding nodes,” he said.

Sunlight itself would help keep the system properly aimed. The constant, gentle push of photons — known as solar radiation pressure — would act on the thin-film solar panels like wind on a weather vane.

“We’re using sunlight not just as a power source, but as part of the control system,” Bargatin added. “Solar pressure is very small, but by using thin-film materials and slightly angling the panels toward the computer elements, we can leverage that pressure to keep the system pointed in the right direction.”

In computer simulations, a single tethered structure could stretch for several or even tens of kilometers and support up to 20 megawatts of computing power — roughly the output of a medium-sized data center on Earth. Instead of one giant facility, the vision is a ring of modular systems circling the planet.

“Imagine a belt of these systems encircling the planet,” added Bargatin. “Instead of one massive data center, you’d have many modular ones working together, powered continuously by sunlight.”

The idea arrives as companies and governments race to build more AI infrastructure. Training and running large AI models requires enormous amounts of electricity, and many ground-based data centers also consume large volumes of water for cooling. Space-based systems powered directly by the sun could ease some of that strain, especially for AI inference — the process of answering user queries with models that have already been trained.

Bargatin argues that many current orbital data center concepts are either too small to matter or too complex to build.

“The problem is that these designs are challenging to scale,” he said. “If you rely on constellations of individual satellites flying independently, you would need millions of them to make a real difference.”

Other proposals imagine huge, rigid structures assembled robotically in orbit, but those would require manufacturing and deployment capabilities that do not yet exist at the necessary scale. The Penn design aims for a middle path, using “tethers,” solar panels and optical communication links that are already well understood.

The researchers also had to confront one of the harsh realities of space: constant impacts from micrometeoroids and tiny pieces of debris traveling at high speeds.

Co-author Jordan Raney, an associate professor in MEAM, noted the team focused less on preventing collisions and more on how the structure would behave after being hit.

“It’s not a matter of preventing impacts,” Raney said in the news release. “The real question is how the system responds when they happen.”

Using simulations, Raney and MEAM doctoral student Dengge “Grace” Jin modeled how repeated impacts would ripple through the tethered structure over time. They found that when a micrometeoroid strikes, it can cause a brief wobble or twist, but the motion spreads along the tether and gradually dies out.

“It’s a bit like a wind chime,” Raney added. “If you disturb the structure, eventually the motion dies down naturally. We had to understand how long that process would take, to be sure that the data center would be stable even when hit by multiple objects.”

The design also builds in redundancy.

“Each node is supported by multiple tethers,” added Raney. “So even if an impact severed a tether, the system would continue to function.”

One of the toughest engineering challenges is heat. On Earth, data centers rely on air or liquid cooling to carry heat away from processors. In space, there is no air, so the only way to shed heat is by radiating it away as infrared light. The Penn concept includes radiators, but the team wants to improve them, aiming for lightweight, durable designs that can handle the intense, continuous loads of AI computing.

The system is not meant to handle every part of AI’s workload. Sending massive training datasets to and from orbit would be slow and expensive. Instead, the researchers see orbital data centers as a way to handle the rapidly growing demand for running already-trained models.

“Much of the growth in AI isn’t coming from training new models, but from running them over and over again,” Bargatin added. “If we can support that inference in space, it opens up a new path for scaling AI with less impact on Earth.”

The next step for the team is to move beyond simulations and build a small prototype with a limited number of nodes, to test how the tethered architecture behaves in practice.

The work, published in arXiv and presented at the 2026 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) SciTech Forum, suggests that a future where some of the world’s most advanced AI systems run far above our heads may not be science fiction, but an engineering challenge within reach.

Source: University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science