In a world-first, a high-tech eye prosthesis developed by Stanford Medicine has restored vision in patients with advanced macular degeneration. Read on to learn about the device’s transformative potential.

In a groundbreaking medical advancement, a tiny wireless chip implanted in the eye and a pair of innovative glasses have restored partial vision to individuals suffering from an advanced form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

The results, achieved through a collaborative international clinical trial led by Stanford Medicine and published today in the New England Journal of Medicine, offer renewed hope to millions affected by this debilitating condition.

The clinical trial showed that 27 out of 32 participants regained their ability to read a year after receiving the PRIMA eye prosthesis. Digital enhancements offered by the device, such as zoom and higher contrast, allowed some participants to achieve reading acuity equivalent to 20/42 vision.

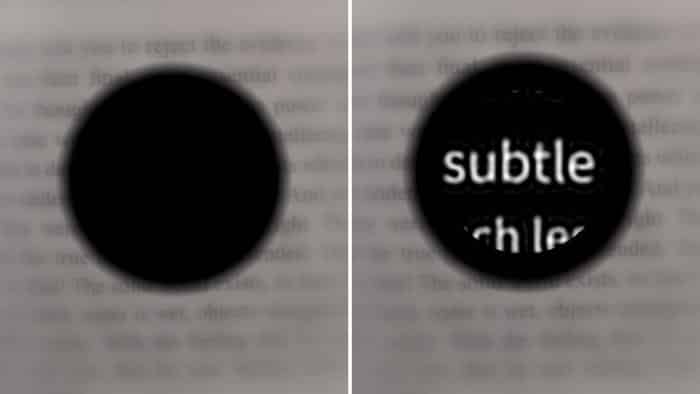

Caption: Left: Simulation of a patient’s vision with macular degeneration. Right: Simulation of the patient’s vision enhanced with the PRIMA eye prosthesis.

Credit: Palankeen Lab/Stanford Medicine

The two-part PRIMA system, developed at Stanford Medicine, comprises a small camera mounted on a pair of glasses that captures and projects images via infrared light to a wireless chip implanted in the eye. This chip converts the images into electrical stimulation, mimicking the function of natural photoreceptors damaged by AMD.

“All previous attempts to provide vision with prosthetic devices resulted in basically light sensitivity, not really form vision,” co-senior author Daniel Palanker, a professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University, said in a news release. “We are the first to provide form vision.”

Age-related macular degeneration, specifically its advanced form known as geographic atrophy, gradually destroys light-sensitive photoreceptors in the center of the retina. While most patients retain some peripheral vision, the PRIMA device leverages any preserved retinal neurons to relay information from the implant.

The 2-by-2-millimeter chip, implanted in the retina where photoreceptors have deteriorated, is sensitive to infrared light projected by the glasses. This ensures the prosthesis operates invisibly, preserving patients’ remaining natural vision.

“The fact that they see simultaneously prosthetic and peripheral vision is important because they can merge and use vision to its fullest,” Palanker added.

In the trial, which involved 38 patients over 60 with severe geographic atrophy, all participants began using the glasses four to five weeks post-implantation. Visual improvements were noted over several months of training, with 27 participants regaining reading ability and 26 demonstrating significant improvements in visual acuity.

One participant’s visual acuity improved by an impressive 12 lines on a standard eye chart. The device proved invaluable for daily tasks, such as reading books, food labels and subway signs. Two-thirds of the trial participants reported medium to high satisfaction with the prosthesis.

However, 19 participants experienced side effects, including ocular hypertension and retinal tears, which were resolved within two months.

The researchers plan to enhance the device further, aiming to provide grayscale to facilitate face recognition, another critical need expressed by patients.

“Number one on the patients’ wish list is reading, but number two, very close behind, is face recognition,” added Palanker.

Future iterations of the PRIMA chip could feature smaller pixels, offering higher resolution and the potential for vision close to 20/20 with electronic zoom. New trials are planned to explore the prosthesis’s effectiveness in other types of blindness caused by photoreceptor loss.

“This is the first version of the chip, and resolution is relatively low,” Palanker added. “The next generation of the chip, with smaller pixels, will have better resolution and be paired with sleeker-looking glasses.”

José-Alain Sahel, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, is the other co-senior author of the study. Frank Holz, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Bonn in Germany, is the lead author.

Source: Stanford Medicine